The Jokers in a Deck of cards - on the ever-evolving Generalist Role

On the ever-evolving generalist/full-stack role and to what extent does it make sense to broaden your skillset.

In our industry, some don’t fit into a single box. Being one of those people, I’ve felt somewhat constrained when hired for a “front-end” or a “back-end” role. I’ve felt more at home in the very vaguely defined “full-stack” role, but those roles can sometimes get a bit overwhelming. While I do enjoy the challenge of learning new things, infra and cloud stuff makes me want to cry. It’s me, AWS; it’s not you.

Now, the benefits of doing the cloudy stuff aren’t lost on me - but I prefer setting my own application server, HTTP servers, etc. I don’t dislike automation, but I like understanding what’s going on “under the hood” without having to wade through pages of (usually not great) documentation or getting consultants that point me towards one of the thousand available methods to load-balance something. Okay, rant over, back to the topic at hand.

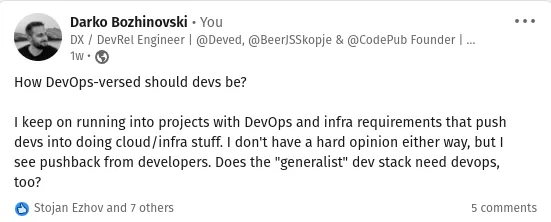

The conversation that sparked this post

What really inspired me to write this post is the following LinkedIn exchange:

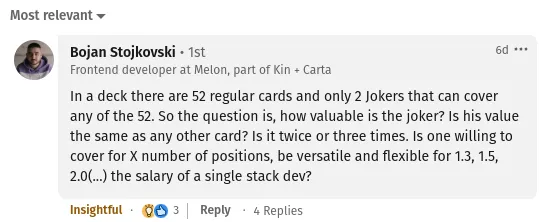

And the comment that followed:

Bojan’s analogy is good and spot-on for multiple reasons. Having a flexible skillset does make you more valuable in the sense that you can jump in at any end of the proverbial stack and fill a role. Does that come with monetary benefits? It’s debatable, but in my experience, it doesn’t make that much of a difference. Should it? I could argue that it should, but that’s a topic for another post.

“Jokers” is an accurate analogy to what the generalist role usually is - a placeholder card, maybe a trump card, depending on the game. This is exactly what a generalist does - fill in a need or provide insights/big-picture ideas for a project.

Being in such a role comes with tradeoffs - some great, some not so much. Let’s dig deeper into those.

The full-stack developer of yore

In the olden days, there was no such thing as stacks. I remember a time when front-end amounted to negotiating with the browser (I haven’t forgiven you IE) not to screw up the HTML, CSS and maybe some JS that you neatly packaged into a page via a templating engine. People who called themselves front-end developers invoked a very different set of ideas about what they did than what we do today. More often than not, there were expectations that you’d be able to do some design work, often using Photoshop - we used to have people that did “slicing”. It totally made sense, though. The web was a very different place than what it is today, tech-wise. So, if you were into web development, you were called a web developer. No front-end or back-end about it, let alone full-stack.

But a chain of events happened that caused two important things: JavaScript got better as a language, and the Web Platform got decent to work with. Naturally, people started doing more and more stuff in the browser - there’s no need to ignore the processing power of an entire machine just because you’re used to sending stuff from the server. So the front-end started taking on a different meaning than what we previously thought. Consequently, the role of a front-end developer started being a thing.

Naturally, those who were into web development but still disliked JavaScript (which, frankly, was often the default) stuck to the back-end. In effect, the classical web developer turned into what we nowadays think of as a back-end developer. This is, of course, simplified and probably biased, but to me, it feels like a good approximation of the evolution of the web developer role.

That leaves us weirdos who liked both sides of the coin. I grew to love JavaScript and the Web Platform a lot, but I still enjoyed doing back-end stuff. Those lucky few of us who loved going back and forth the stack came to be known as “full-stack developers”.

So naturally, when full-stack started being a role companies hired for, the job descriptions were far from standardized (in many ways, they still are). One company may have expected hard-core Ruby-on-Rails skills with a dash of front-end knowledge. Another would expect somebody to write a Backbone.js application and a couple of REST routes in PHP. The job descriptions got broader with the advent of React and modern front-end frameworks in general. This was yet another evolution driven by the modernization of the Web Platform and the rise of JavaScript as a language. With more and more complexity thrown on top of an already complex system, naturally, web development got more challenging to get into and more difficult to master.

Being spread across the stack got even more complicated as a result. Considering the speed at which the front-end changes, plus having to stay on top of your back-end skills, it indeed requires a lot of effort to stay sharp and employable.

As always, things got more complicated. Enter the cloud.

And then, the “cloud” happened

Since everything has to be wEb ScAle these days, and herding servers isn’t the most fun experience in the world, we invented this magical thing known as the cloud. Now, I’m not a cloud skeptic. It has its uses, but it’s not the silver bullet that it’s often made out to be. It’s a tool, and like any tool, it has its upsides and drawbacks. But I digress.

On top of having to know your way across the front and back-end, often there were expectations of full-stack devs who knew their way around the cloud. As a sidebar, we also evolved sysadmins to DevOps, SREs, and infra people due to the advent of the cloud. So, we do have specialized or intersectional roles that deal with the cloud. Regardless, the expectation, explicit or otherwise, is often there - a full-stack person should know cloud stuff on top of an already diverse skillset.

Personally, I never liked the idea of having to deal with the cloud. I can and like setting my apps and servers on bare-metal or on VPSs. Yes, it’s not super-scalable, but the real question is: does it need to be cloud-scale? Quite often, investing in cloud stuff early in a product’s lifecycle just adds complexity on top. But I digress again.

My point is - the full-stack role and the expectations around it got even more complicated.

The generalist role today and tomorrow

So, what does that all mean for the generalist full-stacker today? Depends on the company, but I feel the expectations are broader than ever. With no sign of slowing down. While I feel like we need to redefine what the full-stack means, really, one key thing is that it’s a role that’s constantly evolving. That constant evolution means that we, as generalists, must remain flexible and open to learning new things. Personally, I feel like that’s a good thing - you never really run the risk of getting bored with your “toys”. We all have our limits and ranges of interests (I’m looking at you, cloud). Still, the flexibility and the ability to jump up and down the stack will remain essential for the generalist of today and tomorrow.

The elephant in the room - time and focus shifts

My previous points may paint an interesting picture, but we all suffer from one key constraint - time and, more importantly, the time we dedicate to being focused on one single task. No matter how flexible of a skillset you possess, you still have the same hours in a day as your more specialized counterparts. Shifting your focus from writing CSS to imagining a new feature to writing a REST endpoint has a time overhead - (23 minutes, to be exact)[https://ics.uci.edu/~gmark/chi08-mark.pdf].

On top of that, your energy stores aren’t infinite. I don’t have the scientific research to prove it, but I feel more tired the more I switch context. So you’re left with a choice - either plan for context switches to minimize their cost and time overhead, or you’ll have to embrace the chaos and the overhead that comes with it.

That said, I’m not much of a daily-level planner. My usual operational mode for these shifts is to stick to one task as much as possible, fight against new piling tasks (unless they are super-super urgent, but the burden of urgency proof is on the requester), and ultimately embrace the chaos. It works most days, but it’s far from a perfect system. I’m experimenting with a more structured approach, we’ll see how that goes.

While the point of having a broad skillset and flexibility to be able to jump in and out of different tasks stands, we are limited by time. Strategy is vital, as we are prone to burnout.

The hidden bonus - you can specialize

With ups and downs covered, there’s one key aspect that we didn’t - you can specialize at any time. Being a generalist, you already have at least some basics of a specialized skillset. That gives you an advantage if you decide that you want to specialize in front-end, or back-end, or cloud, or whatever.

This is likely one of the most significant advantages of being a generalist. While nothing is stopping a developer who decided to be a specialist from the get-go to broaden their skills, it’s often a more arduous path to take compared to already having a skillset that you can build upon.

The hidden bonus, 2 - it doesn’t have to be one

Nothing is limiting you from doing it twice. Or as many times as you feel like. In fact, I’d argue that the ultimate full-stack generalist ideal would be “a jack of all trades and a master of some”. Specializing doesn’t cost you flexibility; it simply adds depth to an already existing skill set.

Broad plus deep in some areas is a great combination to have, and it opens up a lot of opportunities.

Takeaway

Being a generalist, or full-stack, or having a broader skillset does come with a set of advantages and disadvantages. It’s not for everyone; it can be energy-consuming, and it can burn you out quickly if you don’t have a strategy. But it’s a rewarding family of roles and a perfect fit for the curious mind that likes to learn new things.

On the other hand, the role also provides a unique perspective, allowing for a greater understanding of the bigger picture in a project. The ability to see and work across the spectrum offers a holistic view that specialists might sometimes miss. This is beneficial not only to the individual but to the teams and companies they work for, as they can provide insights that bridge gaps, improve communication, and optimize processes.

Additionally, the path of a generalist is often a journey of continuous learning. It’s not just about staying updated with the latest technologies or methodologies, but it’s also about understanding how different parts of a system interact and influence each other. This constant need for learning and updating one’s skill set can be a strong motivator for those with an innate curiosity.

For those who thrive on variety, learning, and adaptability, it’s a path worth considering.